10 Questions with Seth John of Growing Oceans

Growing Oceans is a non-profit team of ocean scientists who learn from existing natural processes in the ocean that take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and store it deep in the ocean.

A collaboration between Growing Oceans and Tonga is focused on the process of nitrogen fixation for phytoplankton. Ocean organisms take nitrogen out of the atmosphere and fix it into the form that tiny ocean plants need to grow. As those tiny plants — phytoplankton — photosynthesize, they pull CO2 out of the atmosphere and when they die, they sink to the ocean depths and store that carbon long-term. Plankton are also the base of ocean food webs and support ocean biodiversity and life.

In the South Pacific and around Tonga, there are many ‘hydrothermal vents’, or volcanic cracks where superheated water shoots up from Earth’s crust. That water has iron! This iron acts as a nutrient for the nitrogen-fixing organisms, which in turn stimulate tiny ocean plants over parts of the South Pacific. These hydrothermal vents set in motion a process that takes 15 million tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere every year – providing a way for Growing Oceans to study the process in a natural context.

1. What inspired you to work on this project?

I’ve been an oceanographer my whole career, studying trace metals in the ocean and their impact as micro-nutrients for life in the ocean. In that time, climate change has become a more dire threat to the oceans we’re studying. So we oceanographers have started to wonder: are there ways we can take our knowledge of the ocean and address the climate threat? Oceans are going to be massively impacted by climate change, but can they be part of the solution too? And the specific idea of using nitrogen fixation as part of a climate solution goes back many decades, especially at the University of Southern California, where I work.

2. What do you find compelling about this project? What are you most excited about?

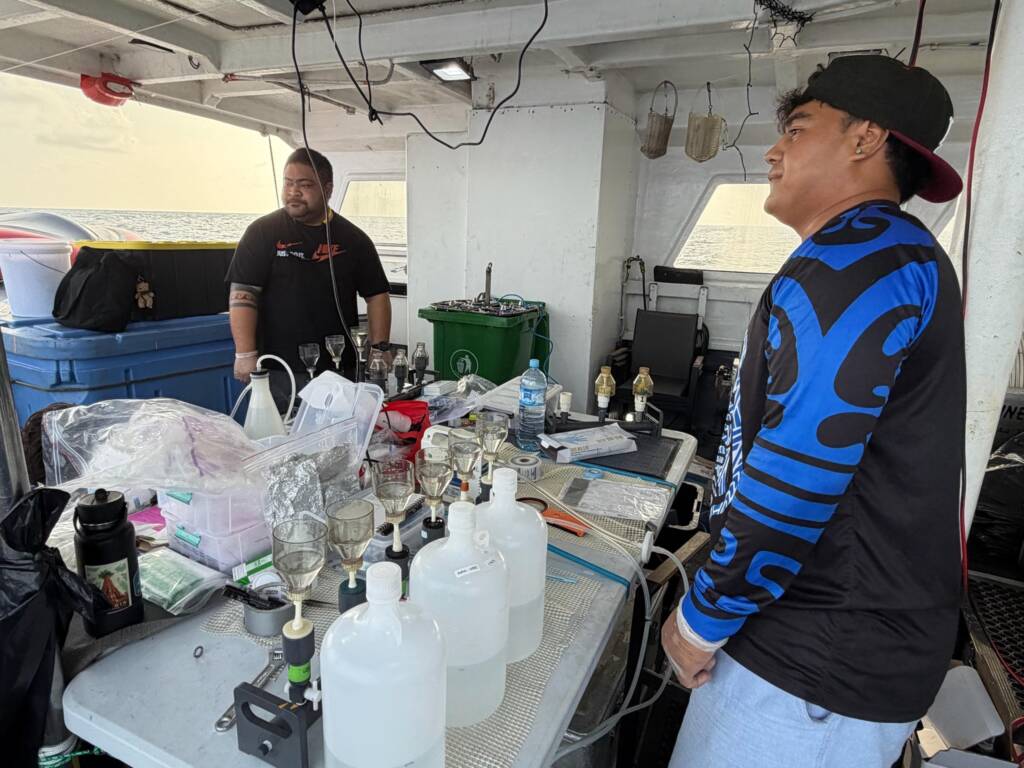

I expected the science itself to be exciting, and it is, but in fact, the most exciting part has been our collaborations with Tonga. Early on we connected with Lord Fatafehi Fakafānua (pictured above, left), who just became the Prime Minister of Tonga. Through him I had an early opportunity to present our work to the government of Tonga. From that early connection, we’ve now been able to connect with people in civil society and the business community there, and with Tongan researchers too. The Tongan people have big goals for restoring their oceans and it’s been extremely positive to learn from them how we academic scientists can collaborate and support their goals. Co-design has been a part of the project from the beginning.

3. What’s your end vision here? What’s your ideal outcome?

We want to fully understand the promise of this approach as a climate solution, while remaining very aware of any potential risks. In theory, every atom of iron added to the surface ocean can pull 23,000 carbon dioxide molecules in the ocean, meaning that there is a tremendous potential for carbon storage and ecosystem benefits. Studying the naturally-occurring process will give us a lot more information about how this process actually plays out in the oceans. The ideal outcome is to develop a clear set of scientific findings, which Tonga and other South Pacific island nations can use to make decisions about how to move forward.

4. Where are you up to now in the process?

The project is new but we’re moving very quickly. We’ve been building a science team in the US and have also been working with our Tongan collaborators about how to operate ‘on the ground’ — or rather, ‘in the water’!

We first travelled to the South Pacific in spring 2025 and we’re back there right now (Jan 2026) conducting our first serious scientific expedition. We have about a dozen people on the team, and along with lots of scientific equipment! We’ll be doing our research from Tongan tuna fishing boats, mapping the hydrothermal plume and mapping the biological response to hydrothermal iron input. And we’re already planning to go back in March for another expedition.

5. What are you hoping to understand with this expedition?

We want to understand the natural response to the iron released by the hydrothermal vents. So we’ll be measuring ecological response, the nitrogen fixers, and even looking at fisheries and birds to see if their populations higher up the food chain are affected. Ecological safety is a focus, so we’ll be checking if there are any harmful algal species growing that could be feeding off the extra nitrogen. The natural input of iron from these hydrothermal vents is happening on a scale of hundreds of square kilometers, so it’s a big task to map and understand the impacts.

This has also been one of our first opportunities to work directly with Tongan scientists from the Ministry of Fisheries and the Ministry of Lands and Natural resources. They’ve been helping us to set up experiments and analyze samples, and they’ve been an extraordinary resource helping us to understand the local ocean environment and ecology.

6. When might you start to add iron?

That’s a decision that will be led by our Tongan partners in the future. It’s their patch of ocean, not ours.

Our partners know the ocean-climate crisis is urgent, and they are motivated to answer the same scientific questions which interest us. But a need to work safely is paramount. We’re trying to balance those two desires: moving as quickly as we can while ensuring a safe and beneficial progression with clear stage gates and off ramps. Ultimately, it’s our role to provide as much information as possible, and a decision for Tongans to make in terms of next steps in research and observation, including, potentially, to observe impacts of iron addition in waters that don’t benefit from this naturally.

7. Speaking of, what are the potential risks of adding iron to the ocean?

The oceans are very complex and the oceans are very special. You have to make sure that you’re proceeding with real care and on the basis of a lot of data.

Theoretically, the iron might trigger harmful algal blooms, some of which are toxic to fish and marine life. Or you could throw the ecosystem into imbalance.

Our starting point is studying the volcanic areas which are already creating a lot of positive benefits for ocean life. They don’t seem to be ecologically degraded by these nutrient additions — if anything, it’s the opposite. Yet, as ocean scientists, it’s really important we monitor for any unintended consequences or risks. So, one of the main things we’ll be watching for are harmful algal bloom species.

We think of our approach as a gentle intervention, but we want to make sure that we’re maintaining South Pacific ecosystems healthy and in balance.

8. What kind of social / cultural / political will and momentum is needed?

This work will be done in Tongan waters. So this needs to be a Tongan project. We’re there by invitation to facilitate the process and provide information, co-design support, and support the capacity of Tongan scientists. Over the long term this is a project that Tongans own. Tonga is the only country in the Pacific that was never colonized: they have a long and proud history of independence that we honor and respect. Only Tongans get to decide what happens in Tongan territories.

9. Are there co-benefits to this? What’s the business case?

It is theoretically likely that boosting the plankton could have beneficial impacts up the food chain, increasing the fish population. We hope that local fisheries will benefit, and we’ll be monitoring for that, though we expect it will take several years to identify the specific impacts.

The other huge impact it could have in Tonga is economic. To the extent that outsiders want to pay to have carbon dioxide removed at scale through nature-based processes, Tongans should be at the front of the line to receive those benefits, and invest them into their national climate resilience fund.

That said, this is so speculative that it’s hard to predict when the time would be right to be scaling. Right now, the goal is to make sure Tongan decision makers have information they need to understand the potential benefits and risks, even of small amounts of iron addition.

10. What do you wish people outside the climate space knew, that those inside the climate space already know?

One thing that I’ve come to understand from being in an Earth Sciences department with a lot of geologists is that the Earth has not always been stable climatically. In past times of great climate change on Earth have been times of enormous ecological disruption. Huge species loss, and shifts in face of life on earth. Over the long run, Earth will be okay, life finds a way, the planet will go on and there will be some future for the planet. But we don’t want to be responsible for forcing one of these dramatic, and honestly very scary times, of climate and ecological devastation and change. We all have an interest in trying to make sure that we treat our planet, oceans, and all life on Earth gently.